Yesterday I offered you a painting by Piero di Cosimo and most of My Daily Art Display was taken up with the story behind the painting and the painting itself without touching on the life of the artist. Today, to make amends, I am giving you not just one painting by Cosimo but two portraitures ,but first, just a little about the artist himself.

Piero di Cosimo, also known as Piero di Lorenzo was born in Florence in 1462. His father Lorenzo was a goldsmith. He was apprenticed to the artist Cosimo Rosseli, his godfather and a painter of the Quattrocento, which takes in the artistic styles and cultural events of the 15th century. It was from Rosseli that Piero di Lorenzo derived his more common name “Cosimo”. In 1481 Pope Sixtus summoned Rosseli to Rome where he was commissioned to decorate part of the Sistine Chapel. Rosseli took Cosimo with him and he helped Rosseli with the fresco of the Sermon on the Mount, painting the background landscape.

In Rome Cosimo developed a love for the Renaissance painting genre completing many works appertaining to Greek Mythology, one of which was showcased yesterday in My Daily Art Display. He is best known for his idiosyncratic paintings featuring fanciful mythological inventions in a world inhabited by satyr, centaurs and primitive men. He was a superb painter of animals and a master of portraiture as one can see by today’s paintings.

Cosimo was an eccentric. He was a solitary person, a loner, who preferred his own company. He didn’t like people to see him at work and would lock himself away for days on end. He was untidy and his studio rooms were dirty but he seemed oblivious to the chaotic circumstances of his life. He also had an irrational fear of fire and rarely cooked his food and he was terrified of thunderstorms. Piero di Cosimo died of the plague in 1522, aged sixty.

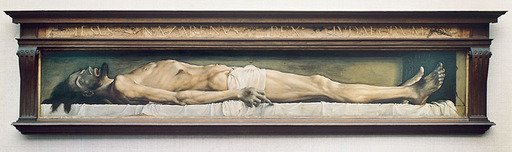

My Daily Art Display today is paired portraits painted by Cosimo. Portraits featuring two people at that time were usually male and female and often man and wife. This set of paired portraits is a rare example of a portrait pair featuring two men, actually father and son, from different generations. They are the only surviving portraits, which have been irrefutably accepted as being the work of Cosimo. Both are wood panel paintings, one is entitled Portrait of Giuliano da San Gallo, Architect (the son) and the other is Francesco Giamberti San Gallo, Musician (the father), a cabinet maker, architect and musician in the service of Cosimo de Medici family. The name “San Gallo” was added later to the family name “Giamberti”. The name derived from the Porta San Gallo, one of the gates of the city of Florence, near which the Giamberti family had their house.

Portrait of Giuliano da San Gallo, Architect by Cosimo was completed in 1482. This highly successful architect and master builder to Lorenzo de’ Medici, the Florentine ruler, stands at a balustrade, turned three-quarters towards the observer. On the balustrade are the tools of his architectural trade, namely a compass and a quill. In the background there is an undulating Tuscan landscape which abuts a mountain range. His appearance is formal and dignified. He looks self-confident and somewhat aloof. Note the detail reproduction of the cloth on the upper part of his sleeve. Note also the effort Cosimo has put in with regards his appearance, the wrinkles around the eyes and the silvery tints in his graying hair.

Francesco Giamberti San Gallo, Musician belongs, like the other portrait, belongs to the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam but has been loaned out to the National Gallery in London. The painting was completed circa 1482 and was commissioned by the son Giuliano on the death of his father in 1480, the intention being that it would form a portraiture pair with his own earlier portrait carried out by Cosimo. The father is painted in profile which gives a clear outline of the face offset against the background. This clear-cut portrait shows an old man with sunken cheeks. He is formally dressed which makes some art historians believe that the father had already died and the portrait was based on the death mask of the father. His face has signs of light gray stubble and we can see the veins on his temple and his ear lobe. His ear is almost bent double by the weight of his hat. As was the case in the son’s portrait the father is side on to a balustrade on which are the “tools of the father’s trade” – not the tools of a cabinet maker or architect but the “tools” of a musician – a sheet of music for Francesco Giamberti often composed music for the Medicis on special occasions.

The two paintings are outstanding in the way the faces contrast sharply against the background landscape and sky. Note the silken cover on the balustrade of both portraits. Observe how the pattern of the striped silken fabric seems to run continuously through both portraits. It is thought that after Cosimo completed the portrait of the father, Francesco along with the tools of his trade he went back to the portrait of the son, Giuliano and added this ornamentation and his “tools of the trade” to his portrait in order to achieve a commonality between the two paintings . So why did Giuliano commission the painting of his father? Was it for him to remember him or is it as some art historians postulate that it was to enhance his own reputation by emphasising his own intellectual heritage and thus improving his own standing as an architect. Maybe that is an unjustified and a cynical view of the situation. You must decide !