My next two blogs deal not with a particular painting but with the subject of a series of paintings completed lovingly by one artist. The subject is Camille-Léonie Doncieux, who was the beloved model, mistress and wife of Claude Monet. In 1861, Monet had enlisted as a soldier in the Chasseurs d’Afrique regiment and spent two years in Algeria. His military life came to an end in 1863 because he had fallen ill with fever. He went back to Paris where he studied at the atelier of the Swiss artist Charles Gleyre and it was during this time that he met up with the artists Sisley, Bazille and Renoir, who would later join together with others and become known as the Impressionists..

Camille Doncieux was born in 1846 and met the impoverished but talented painter, Claude Monet, for the first time in 1865 when she was just eighteen years of age. She came from an ordinary unprivileged background. She fell in love with him, leaving her home to live with the talented 25-year-old painter who struggled to sell his work. People called her La Monette. Everyone she met fell under her spell. It was recorded that she was a ravishingly good-looking girl with dark hair, very graceful, full of charm and kindness. Monet, her future husband, was struck by her beauty and described her eyes as being wonderful. It was not long after they met that she began modeling for him and soon became his favourite model. His professional interest in her soon became personal and the two soon became lovers. The first time we come across Camille in a painting by Monet was in a study for his ill-fated work Déjeuner sur l’Herbe.

In 1863, Édouard Manet had exhibited his painting Déjeuner sur l’Herbe at the Salon des Refusés (see My Daily Art Display, December 23rd 2010). The critics and public were shocked by the work and Manet’s depiction of a nude woman seated with a pair of clothed men in a landscape setting. Monet, who was known for his competitive streak decided to paint his own version of Déjeuner sur l’Herbe in the spring of 1865. This audacious venture would culminate in putting it forward for an exhibition at the Salon of 1866. Following outdoor studies he made in the Forest of Fontainebleau, he immediately headed back to his nearby studio at Chaillyen-Bière and started to make preparatory sketches for what would be his mammoth canvas measuring an unbelievable 4.5 metres x 6 metres. In one of his preparatory sketches, which he did in oil entitled Bazille and Camille (study for Déjeuner sur l’Herbe) we see Camille Doncieux and Monet’s fellow artist friend Frédéric Bazille. Ultimately the painting was not a success. Monet was unable to finish it in time for the 1866 Salon and eventually abandoned the work. He left it, rolled up, with his landlord as part payment for rent he owed but it became damp and all that now remains are fragments of the work and some preparatory studies. The experience did, however, contribute to Monet’s realisation that to portray the brief moment in time, he would have to work on a much smaller scale.

The next time we see Camille is in a painting Monet exhibited in the 1866 Salon. The work was entitled Camille or Woman in a Green Dress and now hangs in the Kunsthalle, in Bremen. After his disastrous attempt to emulate Manet with his painting of Déjeuner sur l’Herbe this work of his gained him critical acclaim. Rumour had it that in his rush to meet the Salon deadline he completed the work in four days but one must doubt that assertion. It is not strictly a portrait of Camille. It is all about the dress. She was simply his model for the painting. The first thing which strikes one as we look at the work is the colour of the promenade dress which had probably been borrowed for the occasion. Monet loved colour and the green he has used is awesome. It dominates the painting and even detracts from the woman herself. This is not about Camille but on the dress she wears and how it hangs. The painting reminds one of a photograph out of a fashion shoot for a fashion magazine when the clothes are the important thing and not the model. Look how the background is undefined. It is simply plain and dark. Monet had decided that nothing should deflect our gaze from the woman and her dress. I like how Camille is just raising her right hand towards her face as if the picture has captured her just about to do something, a fleeting gesture, and we are left guessing as to what. Maybe she is adjusting the ribbon of her bonnet. The painting was accepted by the Salon jury and hung in their 1866 exhibition. It was an immediate hit with both the art critics of the time and the public and the Paris newspapers called Camille the Parisian Queen.

One amusing anecdote about this painting was the story that Monet’s signature on the painting had been mistaken by many viewers for that of Manet, who had entered the Salon to a chorus of acclaim for his supposed work. Monet told this story to the newspaper Le Temps:

“….imagine the consternation when he discovered that the picture about which he was being congratulated was actually by me ! The saddest part of all was that on leaving the Salon he came across a group which included Bazille and me. ‘How goes it?’ one of them asked. ‘Awful,’ replied Manet, ‘I am disgusted. I have been complimented on a painting which is not mine’…….”

That same year Monet produced a hauntingly beautiful and intimate portrait of his lover entitled Camille with a Little Dog, which is in a private collection. We see Camille sitting side-on to us in quite a formal pose. This is one of the few paintings of her by Monet that looks closely at her. Once again as was the case in the Woman in a Green Dress, the background is plain and dark and in no way serves as a reason for taking our eyes off Camille. We are not to be distracted from her beauty. This painting is all about Camille. It is interesting how Monet has painted the figure of the dog simply by thick brush strokes. At a distance it looks like a dog but if you stand close up to the painting you can see it is just a mass of brush strokes. However Monet has not treated the painting of Camille’s face with the same quick thick strokes of his brush. She has been painted with delicate precision. Monet did not want to depict the love of his life with hastily swishes of a brush. He took pains in her appearance. This was a labour of love.

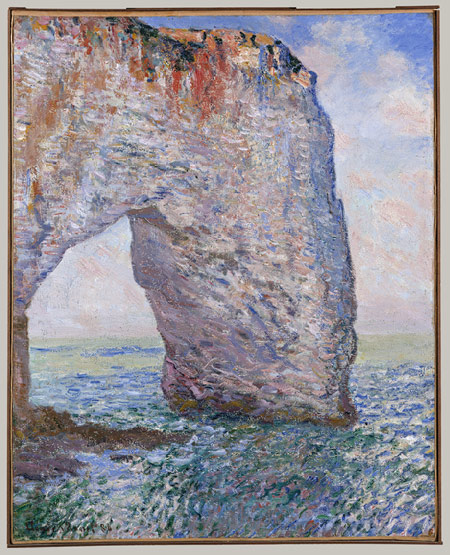

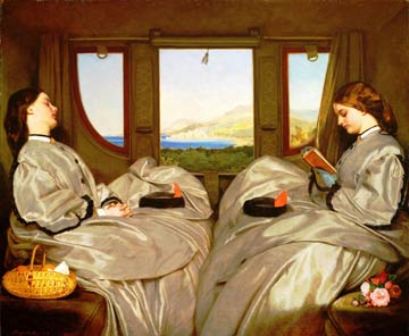

In 1867 Monet’s lover Camille gave birth to their son Jean. A year later, during the winter of 1868, Monet started on his painting entitled Luncheon, which can be seen at the Städelsches Kunstinstitut in Franfurt. This family, which now included their son Jean, were staying in Étretat at the house of a patron, where Monet had taken refuge from his Parisian creditors and critics. It is a large highly detailed oil on canvas painting measuring 230cms x 150cms. It is simplistic in its subject. Before us we have sitting at the dining table Camille and her blonde-haired son. She looks lovingly at him whilst he seems to only have eyes for the food. A visitor stands with her back to the window and the maidservant is seen leaving the room. A place is set out ready for her husband to join her at the meal table. Look how Monet has painted a number of items overlapping the surfaces they are resting on. On the table we have the loaf of bread, the newspaper and the serviette all hanging over the cloth which Monet has depicted as being somewhat creased. In the background we have two books overlapping the edge of the table. All this in some ways adds to the realism of the painting. Sunlight pours through the large window to the left of the painting and bathes the well-stocked table in light and by doing so brings it to life. Monet submitted the painting to the 1870 Salon jury but it was rejected. Four years later he included the work in the First Impressionist Exhibition in 1874.

to be concluded tomorrow………………………………