When I look back on the four and half years of doing this blog I see my early entries were quite short but appeared nearly three or four times a week. Nowadays due to other commitments and my being sucked into the life of artists the blogs are longer and often in multiple parts. My last three blogs looked at the life of the American genre painter, William Sidney Mount and today I start a multiple-part blog on a home-grown nineteenth century English painter Frederick William Elwell, who many of you, like me, may have up to now, been unheard of. In a way you have to thank my wife for this look at Frederick Elwell as she persuaded me to go with her to Yorkshire for a big three-day cooking event in Harrogate and I managed to slide out of the culinary arena and visit some small local galleries in this beautiful town, where I came across a book on Frederick William Elwell.

Frederick William Elwell was born at St Mary’s Cottage in the small Yorkshire market town of Beverley in on June 29th 1870. His father, James Edward Elwell, was a well-known and well-established wood carver who played a prominent role in Beverley society. In 1900 he was a member of the town council and mayor of Beverley. And when he held the position of Chairman of the Library Committee, he organised the first exhibition of paintings in 1910. The exhibition featured a selection of art which the town had loaned from local collectors. It also included a large selection of works by his son Fred.

Fred Elwell’s schooling began with his attendance at Beverley Grammar School but in 1878 the education establishment had to close temporarily and Fred’s parents had to decide where their son should next be schooled. The family were already aware that their eight year old son was talented at drawing and his father trained him in draughtsmanship and so his father decided to look for some scholarly opening which would allow Fred to further train in art and maybe later architecture as well as attain an all-round education. The decision was made to send Fred to Lincoln to live with his two aunts, and by doing so, it would allow him to attend Lincoln Grammar School and at the same time afford him the chance to enrol in evening art classes at the nearby Lincoln School of Art on Lindum Hill. Fred’s two aunts were a formidable pair of Victorian ladies. One was the principal of the Lincoln Training College for Women whilst the other acted as its secretary

Elwell proved to be a talented scholar and although his father wanted his son’s career path to head towards architecture Fred was in love with painting. He was so good that he was awarded the Gibney Scholarship, named after Rev. J.S.Gibney the canon of Lincoln Cathedral who with others founded then Lincoln School of Art in 1863, and this allowed him to continue on with a three year course in art. In 1887, aged seventeen, Fred Elwell won the Queen’s bronze medal in the National Art School’s competition for his painting, Still Life with Fish. This painting by the seventeen year old Elwell shows the dawning of a great artist in the way he depicts different textures in the painting, such as the shiny reflective glass bottle in contrast to the dull matt finish of the red lobster. On the wall in the background he has depicted fading Delft tiles. The head of the codfish, with its mouth open, is well illuminated against a dark background. Its body is curved and the head turns to the right whilst its tale disappears into the darkness. The curve of the fish is, in some way, countered by the dried herrings which hang in front of the tiles with their tales curving towards the left, balancing out the body position of the cod. Elwell has used the old artist’s trick of depicting depth by incorporating the edge of the marble shelf in the foreground of the painting. This picture is housed in the East Riding of Yorkshire Council Museum.

The head of the college at the time of Fred Ewell was Alfred George Webster and he was a great admirer of the French Impressionism movement which had come to being in the early 1860s in Paris and it was Webster who taught the Impressionist technique to his students. This introduction of Impressionist techniques to students, including Ewell, was strongly opposed by the Royal Academy.

In 1889, at the age of nineteen, Fred Ewell left the Lincoln Art College and followed the path of many aspiring painters of the time and, financed by his father, Fred travelled to Belgium where he enrolled at the prestigious Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp which had been founded in 1663 by David Teniers the Younger. Fred Elwell and a fellow student Claude Rivaz shared a city studio on the Rue des Aveugles. For many this establishment was considered the most important training academy for those artists who wanted to hone their artistic skills and follow classical Academic training. Many great artists, such as Van Gogh, Lawrence Alma-Tadema and Ford Madox Brown at one time studied at this establishment. It was here that the students would learn more about the great Masters of art and in fact the Academy itself housed many works by the old Masters. Fred Elwell’s tutor at the Academy was the landscape and portrait painter, Piet Van Havermaert. Havermaert pressed his students hard and would not suffer any slackers, once telling his students:

“… Always remember that for the money your father pays to keep you here, he could keep four pigs…”

Havermaert was a hard task master and pushed his students to the limit demanding more and more from them.

Elwell flourished under this strict teaching regime and during his final year at the Academy produced a genre piece which harked back to the typical type of art that was so popular in the Low Countries in the seventeenth century. It was entitled The Butler takes a Glass of Port. The title is a play on words, meaning, on one hand, the partaking of a drink but, on the other hand, meaning “stealing” a drink. The scene is set in a dining room and we see the butler, emerging from the shadows. He had just finished serving his master and guests at the dining table and has come to arrange the clearance of the plates. However he has decided to help himself to a small glass of his Master’s port. Look at the miscreant. Look how his face is lit on the side by the candlelight. This use of light was very popular with the Dutch genre painters of the past and Elwell, even at the young age of twenty, managed to master the art of dramatic lighting. Look at the butler’s expression of anticipation as he pours himself a drink. His nose has been given a reddish tinge suggesting that he and alcohol were old friends. It is amusing to note that the painting’s alternative title, another double-entendre, was All Things come to the Man who Waits ! It was at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp that Elwell began to perfect his skill in portraiture and still life through the influence of the work of 17th century Dutch and Flemish artists.

This Academy was also a stopping off place for art students who headed for the artistic academies of Paris, a route that Fred Elwell and his friend Claude Riaz, followed in 1892. The two young artist found themselves some rooms in rue de Campagne Première, on the left-bank, in the city’s 14th arrondissement of Montparnasse. Elwell was fascinated with the French capital and soon built up a large collection of sketches of all that he saw of Paris life. Elwell enrolled at the Académie Julian and was fortunate to be tutored by a giant among artists, William-Adolphe Bouguereau. It was whilst study at the Academy that Fred Elwell started his training in life drawing using living models . He was never given the opportunity to sketch nude men and women whilst studying at Lincoln, probably because of the presence of the cathedral in the city, the Academy thought life classes were somewhat inappropriate. Out of this training came one of Elwell’s finest early paintings entitled Dolls or Léonie’s Toilet.

Léonie’s Toilet was completed by Elwell in 1894. Fred Elwell was introduced to the sitter of this painting, Léonie, by Thomas Warrener who was a friend of his from Lincoln, who, like Elwell, had studied at the Lincoln Art College. Warrener then attended the Slade School of Art before moving to Paris and the Académie Julian where the two friends met up once again. Léonie was also a model for some of Warrener’s paintings. To the left of the painting in the foreground is the washbasin, draped over which is the newspaper famed for its gossip, Gil Blas, which leads us to believe Elwell was interested in the comings and goings in French society. The periodical often serialised French novels as well as being known for its opinionated arts and theatre criticism. Another hint of Parisian life in the 1890’s is the two Japanese dolls hanging from the mirror. Japonisme was sweeping through Europe in the second half of the nineteenth century. It was the term used to describe the influence of Japanese art and fashion on Western culture, and was particularly used to refer to Japanese influence on European Art and Impressionism. This painting’s original title was Dolls, referring to the dolls seen in the work. Sibylle Cole in her 1980 book, FREDERICK W. ELWELL, R.A. 1879-1958. A Monograph with eight selected prints in colour describes the skill of Elwell in the way he has painted the naked back of Léonie. She highlighted the way in which he used a wide range of whites and lovely soft edges where she says “the light leaks into the background”. There is an interesting story behind this work. Elwell, like all struggling artists, had to part with his beloved depiction of Léonie, giving it to his landlord as payment for his rent. Fifty years later the artist James Bateman R.A. was walking down Kings Road in Chelsea when he saw the painting of Léonie in an antiques shop. He bought it and gave it to the seventy year old painter. Elwell was delighted to have Léonie back with him !

The subject, a girl powdering her face, may have come to Elwell after seeing Georges Seurat’s 1890 work, Young Woman Powdering Herself, a painting depicting Seurat’s secret lover, a working-class woman, Madeleine Knobloch. The painting was exhibited at the Société des Artistes Indépendants in 1892, the year Elwell arrived in the French capital.

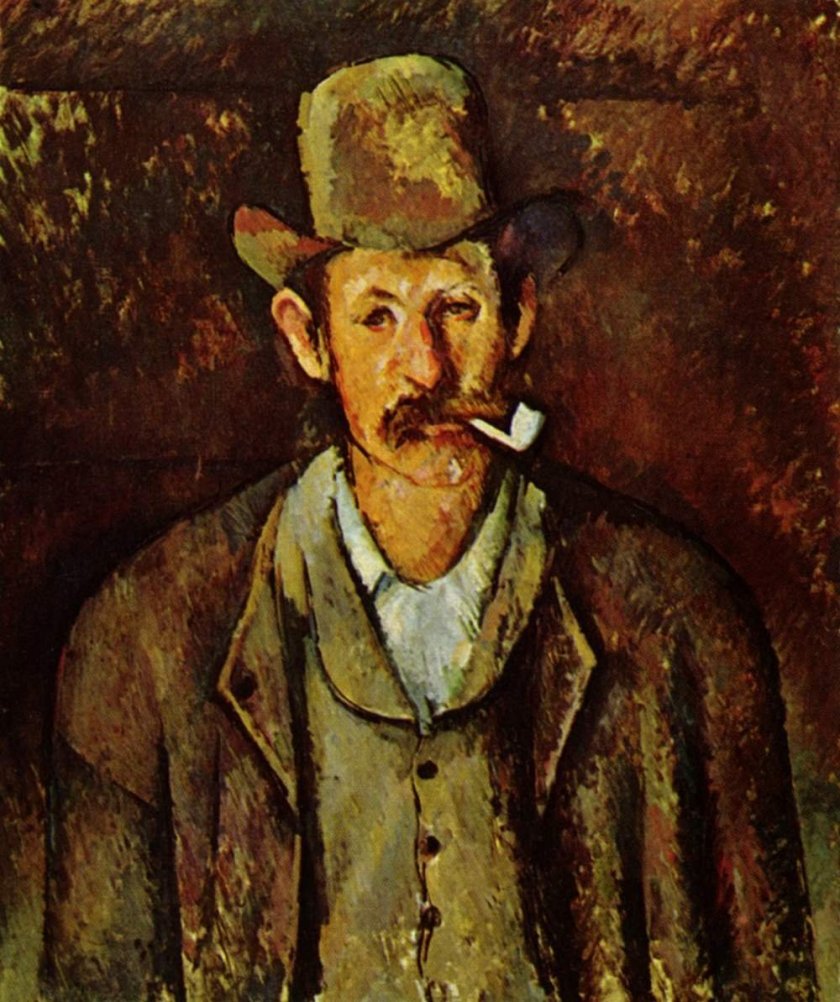

My final offering in today’s blog could well have derived from a Cezanne painting Elwell may have seen, one which was painted by Cezanne in 1892 entitled Man with a Pipe, a depiction of a peasant relaxing, staring out at us with his pipe in his mouth.

Fred Elwell completed a work in 1898 which was entitled Old Man with a Pipe and depicts a gardener, with pipe in mouth, which projects towards us. It is a somewhat cut-off painting with the man’s right fist which grasps the handle of the rake and his left elbow, almost cut out of the lower part of the composition

In my next blog I will continue with Elwell’s life story and look at some more of his beautiful works of art.

Most of the information for this blog was gleaned from the excellent book I bought in Harrogate, Fred Elwell RA – A Life in Art by Wendy Loncaster & Malcolm Shields. It is a beautiful book and well worth buying.

absolutely superb paintings (those of Elwell!) As you know, I love this approach you take – giving flesh to unknown names. Coincidentally I finished the draft today of the 2nd edition of my booklet which introduces European to Bulgarian Realist Art – “Exploring Bulgaria – an aesthetic romp”

Click to access e475c8_fd7c4c7e0f7d4854a99258c89111850f.pdf

it’s appropriate you’re the first to see it.

This guy is so English. I love England so very much and it made me homesick, altho I’m not English. This artist has so many different styles. I don’t know if you mentioned this, because I didn;’t read your blog; I only looked at the paintings. He’s just so wonderful.

The comparison to Leonie with the dolls and Seurat’s lover is intereating and I know how Van Gogh was so taken by the Japanese during that time. I loved the picture in the background of Seurat’s painting of the man and the option of the shutters in case anyone came over that she did not want them to see she could close them.