My artist today is the French nineteenth century painter Jacques Joseph Tissot. In the introduction to Tissot’s biography by Christopher Wood, he writes:

“…Tissot was an assiduous and highly competent painter, most of whose pictures are of pretty, elegant women; his work is visually attractive, without being too demanding intellectually…”

It is that last phrase which is probably the reason that Tissot’s work was loved by the public but was panned and scorned by the art historians and art critics. His country of birth, France, look upon him as just a minor artist saying that his work is too anglicised. It probably rankles with the French art critics that Tissot spent eleven years in London during which time most art historians believe he produced his finest work and accordingly was a financial success.

Jacques Joseph Tissot was born on October 15th, 1836 in Nantes, which, at the time, was a prosperous seaport on the Loire estuary. He was the second of four sons. His father was Marcel Théodore Tissot and his mother, Marie Tissot (née Durand). His father, who was born in 1807, came from Trévilliers, a small mountain village in the Franche Comté region of eastern France, close to the Swiss border. As a young man Marcel left home to seek his fortune and through his hard work was a very successful man. He met and married his wife, Marie Durand, a Breton lady, and daughter of an impoverished royalist family. Marcel and Marie set themselves up in the drapery business and she began to design ladies’ hats. So successful were the couple that in 1845 they returned to Marcel’s birthplace and bought themselves a substantial estate, Chateau de Buillon near Besançon.

Jacques Joseph Tissot was brought up in the family home in Nantes. During his early life Tissot inherited a number of traits which were to help him through life. From his father he acquired a business acumen which was to serve him well during his life and make him one of the shrewdest and financially successful of all the nineteenth century painters. From his mother, who was a very pious Catholic, she instilled in him religious feelings which were to change the course of his later life. His parents through their drapery and design business instilled in their son his love of female fashion and elegance. His final great influence was the port of Nantes itself. For a young boy the port and its ships must have been awe-inspiring and many of his paintings completed whilst living in London thirty years later featured scenes of ports and the ships. Nantes was also blessed with great Medieval and Gothic architecture and young Tissot often sketched the buildings and in fact his early career choice was to become an architect.

He was educated at a Jesuit boarding school but proved to be just an average student. At the age of seventeen he had set his mind to becoming an artist and as was the case in so many stories about artists, his parents were dead set on opposing his choice for his future. His father was adamant that his son’s proposed choice of career was a total waste of time and, but for Tissot’s mother, her son would not have been able to follow his favoured profession.

In late 1856, at the age of twenty, Jacques Joseph Tissot travelled to Paris to embark on artistic training. His two main tutors were Louis Lamothe, the history painter with whom Tissot studied both Italian and Flemish Primitives at the Louvre and spent many hours copying them. He also studied under Jean-Hippolyte Flandrin. Flandrin’s most celebrated work was his 1836 painting, Jeune homme nu assis au bord de la mer (Young Male Nude Seated beside the Sea) which he completed whilst in Rome during his five-year stay, which was granted to him for winning The Prix de Rome in 1832. Tissot spent a short time attending the Ecole des Beaux Arts and it was here he became a close friend of James McNeill Whistler and it was through him that he met the leading French artists of the time such as Fantin-Latour, Alphonse Legros and Gustave Courbet. Whistler also introduced Tissot to a number of English painters such as Edward Poynton and George du Maurier, the illustrator and novelist. It is widely believed that Tissot’s friendship with Whistler and his English friends made him change his name to the anglicised version, James Tissot

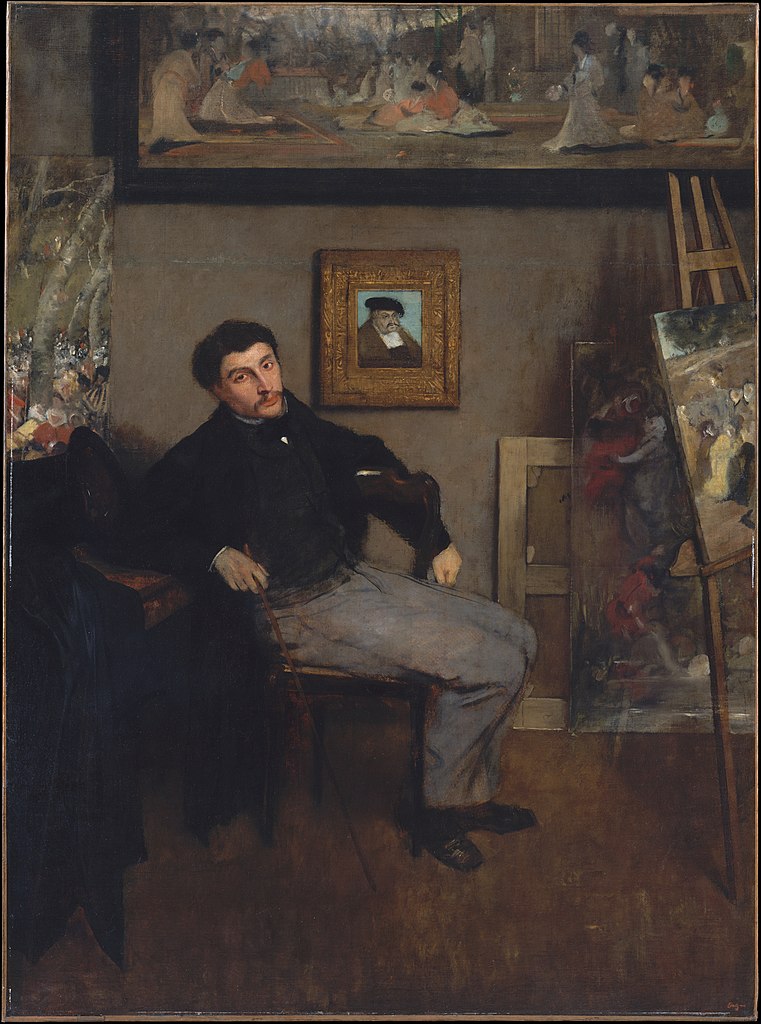

Another of his friends was the Impressionist painter Edgar Degas who painted a portrait of Tissot in 1868. Theirs was a stormy relationship which came to an abrupt end in 1895 when Degas discovered that Tissot had sold one of Degas’ paintings which had been given to him by the artist as a gift. Degas may also have been a little jealous of Tissot’s success in his art sales which were far greater than his own.

Tissot was now seeking new subjects and a new mode of painting and was strongly influenced by the work of the Belgian painter and engraver Jan August Hendrik Leys (Henri Leys), who was a leading representative of the historical or Romantic school in Belgian art. Leys was notable for his history and genre paintings which were often referred to as style troubadour which was a somewhat mocking term for French historical painting of the early 19th century with idealised depictions of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. This was also a style favoured by the young Alma-Tadema who was, at the time, based in Antwerp.

Leys won a gold medal at the Exhibition Universelle in Paris in 1855 for his historical painting Les Trentains de Berthal de Haze (The Trental Mass of Berthal de Haze). A trental mass was a Roman Catholic mass for the dead on the thirtieth day after death or burial. The art critics appreciated the high quality of his reconstructions of times past through his beautiful depictions of early costumes and architecture, as well as the true-to-life postures and facial expressions of his characters combined with the vividness of the colours he used.

From 1859 and for the next five years Tissot paintings featured depictions of historical and religious scenes, many of which derived from Goethe’s Faust. Such depictions were very popular at the time and paintings featuring these subjects were often exhibited at the Paris Salon and London’s Royal Academy. Tissot incorporated, in a number of his paintings, scenes from Faust and Marguerite, an 1855 romantic opera, which was popular with a number of painters, such as Ari Scheffer. The libretto was written by Michel Carré and loosely based on the Faust legend, but simply focuses on Faust’s romantic encounter with Marguerite (Gretchen in Goethe’s original drama) and the tragic results of their liaison. The character of Marguerite was looked upon by the French public as a romantic but ill-fated figure who was a vulnerable victim of her fate.

Although the public may have liked these works which appeared at the Paris Salon the art critics were less impressed, nevertheless one of Tissot’s first “Faustian” paintings, The Meeting of Faust and Marguerite attracted the attention of an important patron, Comte de Nieuwekerke, a high-level civil servant in the Second French Empire. who persuaded the French government to buy the painting for the Musée de Luxembourg. This was such an honour for Tissot as up until then he had never achieved a medal for his works exhibited at the Salon.

Tissot was not deterred by criticism of his Henri Leys painting style and continued with his historical paintings. In 1861 he entered two of his works at the Salon. One, which he completed in 1860, was entitled Martin Luther’s Doubts. In this depiction by Tissot we see the gloomy figure of Luther leaning against a stone pillar, seemingly lost in thought, and completely isolated from the congregation. It is a depiction of the alienation of the man and this theme of estrangement featured in many of Tissot’s works. This is a depiction of a man, termed as a heretic, who openly rejected several teachings and practices of the Roman Catholic Church three centuries earlier.

His second work at that year’s Salon was a more unusual painting entitled Voie des fleurs, voie des pleurs (Way of Flowers, Way of Tears), often referred to as the Dance of Death. This is an amazing composition with all the figures silhouetted on a hillside with the skeletal figure of Death with his billowing white shroud, bringing up the rear with a coffin slung on his back. Although a very theatrical depiction it was one of only a few of Tissot’s early works which was well-liked by the art critics.

Buoyed with the success and the sale of his Faust and Marguerite painting, Tissot decided to carry on with his historical style paintings and in 1863 produced three large-scale works for that year’s Salon, one of which was The Return of the Prodigal Son. It is a remarkable multi-figured painting which is part biblical (the story) part theatrical as the setting looks like a theatre stage set with its medieval buildings. It is a pure Henri Leys-style of painting and one of the last of the type Tissot would complete. The critics on both sides of the Channel were unimpressed. The critic of the London art’s Journal, The Athenaeum stated that it was affected, false and artificial and went on to rebuke him saying that he was wasting his talents by imitating so bizarre a school of painters as that of ancient Flanders. That was the final straw as far as Tissot was concerned and he decided to abandon the Middle Ages for his depictions and instead concentrate on modern life.

Twenty years later however, he did return to the subject of the Prodigal Son with his 1882 work, The Return of the Prodigal Son in Modern Life: The Return, in which he depicts the prodigal son returning repentant to his father, in a contemporary context. The son’s ship has just come in and his father awaits him at the quayside. This painting is now housed in the National Gallery of Art, in Washington DC.

..…………….. to be continued

Most of the information I am using comes from Christopher Wood’s 1986 biography of Tissot which is an excellent read, full of beautiful pictures.

Without any support from his father, Tissot was very fortunate that Whistler, Fantin-Latour and Courbet were there for him. I hope he thanked Whistler in 1871 when Tissot moved to Britain and met rising stars like Edward Poynton. The Franco-Prussian War must have been terrible 😦