Having decided to escape the cold and miserable weather of Britain for a short period I find myself in the warmth of the Algarve soaking up the sun and staring out at the blue sky and sea whilst reading about blizzard and gale-force conditions back home. Ok, that’s enough schadenfreude for one day. However, it is my location that leads me on to the next few blogs – not the Algarve but its neighbour Andalusia which I visited last week and enjoyed the delights of the beautiful city of Seville. I think I was most impressed by the city’s architecture and it is a timely reminder for me to walk more upright and look above eye level instead of concentrating on the pavement – old age can be a challenge!

I always try and visit at least one art gallery if I visit a large city so when I arrived in the Andalusian city of Seville and after settling into the hotel, I headed for Museo de Bellas Artes de Sevilla. Some art galleries/museums can be large and soulless with just a never-ending series of rooms. I particularly like ones, which are different and have had a usage prior to becoming a museum, such as a place of residence or a religious institution, which then come with ornate decorations.

One of the best I have visited was the Museo Sorolla in Madrid which albeit smaller in size in comparison to the much bigger art institutions in the city and, despite featuring only the works of Joaquin Sorolla, it was a true joy to behold and one I insist you visit when in the Spanish capital. The building was originally the artist’s house and was transformed into a museum after the death of his widow, Clotilde, in 1929. The museum was eventually opened in 1932.

The Museo de Bellas Artes de Sevilla was originally home to the convent of the Order of the Merced Calzada de la Asunción, founded on the site by Saint Peter Nolasco, shortly after the re-conquest of Seville by the Christians in 1248. The building itself was built in 1594, but did not become a museum until 1839, following the desamortizacion, the name given to the Spanish government’s seizure and sale of property, including from the Catholic Church, from the late 18th century to the early 20th century which resulted in the shutting down of religious monasteries and convents. The building we see today, with the galleries arranged on two floors around three quiet courtyards and a central staircase, was largely the work of Juan de Oviedo y de la Bandera.

This superb art museum has been lovingly restored and it now ranks as one of the finest in Spain. It is built around three patios, which are decorated with flowers, trees, and the distinctive Seville tile work. Much of the paintings in the permanent collection was Religious Art. Because of Spanish unwavering obedience to the religious teachings of Rome, it was therefore not surprising that their artists were heavily involved in spreading the Christian message through their commissioned works of art. The purpose of religious art and architecture was to gain converts to the Catholic faith. Architecture in the shape of breathtaking cathedrals was, therefore, the principal form of inspiration. Inside the cathedrals and churches statuary was also inspirational and religious stories were illustrated in the form of stained glass windows, altarpieces, and works of art.

Inside, the museum’s permanent collection of Spanish art and sculpture from the medieval to the modern focuses on the work of Seville School artists, such as Bartolome Esteban Murillo, Juan de Vales Leal, and Francisco de Zurbaran.

The large (308 x 402 cms) painting Sagrada Cena (Holy Supper) by the Renaissance painter Alonso Vazquez is part of the permanent collection. It was his first known work and was commissioned for the refectory of the Cartuja de Santa Maria de las Cuevas de Sevilla in 1588. The composition is based on different prints, living the naturalistic elements of the tableware and food. The Mannerist style of the work features the elongated fingers and hands and the emphatic and animated gestures of those at the table all adorned in artificially-coloured clothing.

There were a number of religious paintings by the sixteenth-century Spanish artist Francisco Pacheco including his 1610 painting St Francis Assisi.

Works were on show by Luis de Vargas, the 16th-century painter of the late Renaissance period, who spent much of his life in Seville although he did travel to Rome where he was influenced by Mannerist styles. Such works are characterized by the exaggeration or alteration of proportions, posture, and expression. He was not only a great painter, but was also a man of strong devotional temperament, and was known as a holy man. His greatest wish was to use his talent for the glory of God, and he had a tradition of going to confession and receive Holy Communion before painting one of his great altarpieces. One of his contemporaries said that Vargas kept a coffin in his room to remind him of the approach of death.

One of his paintings on view at the museum was The Purification of the Virgin. In this work we see Mary depicted inside the temple, presenting the baby Jesus to the priest, San Jose. The depiction is completed by the inclusion of three women and a young girl with two pigeons in a basket, together with some angels. This painting records the ceremony of the Purification of the Virgin and the Presentation of the Child Jesus in the temple and festivity celebrated this event occur on February 2nd, which is forty days from the twenty-fifth of December, the date of birth of Jesus. This forty day period harks back to the Mosaic law, which states that the woman who gave birth to a man was impure for a period of forty days, (eighty if the one born was female!). At the end of that forty-day period, the baby had to be presented to the priest in the temple, so that he could be declared clean by means of an offering. As for the offering the mother was expected to offer the priest a one-year-old lamb. However, Mary, being from a poor family, was unable to offer a lamb, and so instead of a lamb, Mary offered the priest a pair of pigeons.

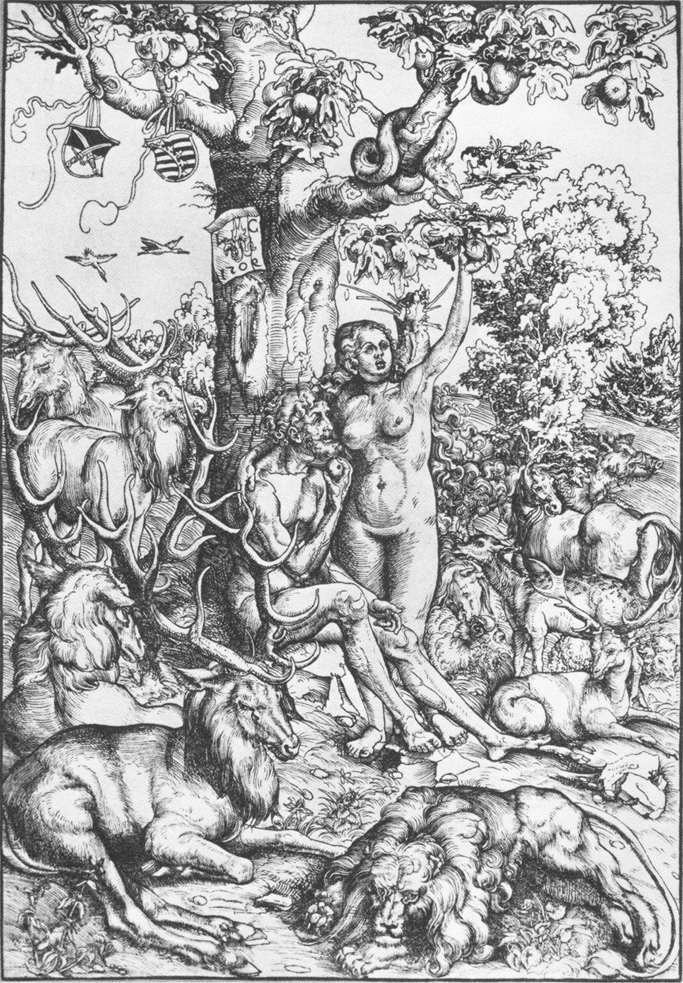

The 1538 work entitled Calvario con el centurión (Calvary with the Centurion) by Lucas Cranach is also part of the museum’s permanent collection. At the heart of the depiction we see Christ on the cross, on either side of him are the in-profile portrayal of the good thief, Dismas, and the evil thief, Gestas, both of whom are also impaled on their crosses. The depiction is at the very moment that Jesus raises his head skywards and utters the words “Father in your hands I commend my Spirit” and it is those very words (vater in dein hendt befil ich mein gaist) we see written in Cranach’s native tongue, at the top of the painting. Look at the amazing way Cranach has depicted the facial expressions of the three men. In the central foreground, we see the centurion atop his rearing horse. He utters the words “Truly this Man was the Son of God” and again the words in German “Warlich diser mensch ist gotes sun gewest” can be seen as if coming from his mouth. The background of this work is quite interesting. Cranach has split it in two. The upper part, which is the sky, is dark and filled with a sense of foreboding whilst the lower background is a distant view of the city of Jerusalem.

One of the two most famous Sevilla-born artists was Diego de Siva y Velázquez, who was born in the Spanish city in 1599. Some of his paintings were displayed at the Sevilla museum and I particularly liked his 162o painting, St Ildefonso Receiving The Chasuble From The Virgin.

Saint Ildefonsus, a scholar and theologian, was born in Toledo around 607 AD. Ildefonse, against his parents’ wishes, gave up their clerical plans for him and he became a monk at the Agali monastery in Toledo and in 650 he was elected to head the order as their abbot. On December 18th 665, according to a biography on the saint in the Catholic Encyclopaedia, he experienced a vision of the Blessed Virgin when she appeared to him in person and presented him with a priestly vestment, to reward him for his zeal in honouring her and it was this event that Velázquez captured in his painting. According to legend, Bishop Ildefonsus and the congregation were singing Marian hymns when light cascaded into the church, terrifying the congregation and causing most of them to flee. The bishop and a few of his deacons remained and they watched as Mary descended and sat on the episcopal throne. She was full of praise for Ildefonsus’ devotion to her and vested him with a special chasuble from her son’s treasury, which she instructed the bishop to wear only during Marian festivals.

The highlight of my tour around the museum was not just witnessing the permanent collection but happening to arrive during a special 400th-anniversary exhibition of one of Seville’s most famous painters. Who was he? I will tell you in my next blog………..