Tissot, heartbroken at the death of his lover and muse Kathleen Newton, returned to Paris in November 1882. It was on his return to France that he competed a large family portrait painting entitled The Garden Bench. Kathleen Newton is depicted in Tissot’s London garden bathed in sunlight, sitting on a garden bench which is draped with a fur rug. She looks lovingly at her son Cecil George whilst behind her are her daughter Violet and her niece Lilian. With the premature death of Kathleen this painting became special to Tissot and although he allowed it to be exhibited in Paris in 1873 he would not allow it to be sold and kept it until his death.

That same year he completed another work depicting his “family” playing in the garden of his home, which no doubt would remind him of the joys he experienced with Kathleen and her children which were suddenly and tragically taken from him. The painting was entitled A Little Nimrod. His period of family life was over and would never return. So, after eleven years in England Tissot was once again on French soil. He was heartbroken and even the French writer and art critic, Edmond de Goncourt, who had castigated Tissot for his art work, was moved by Tissot’s anguish. After meeting with him, de Goncourt wrote in his journal:

“…A visit today from Tissot, just arrived in the night from England – and who told me during our talk hat he was much affected by the death of the English Mauperin, who, though already ailing, served as a model for the illustrations in my book…”

Edmund de Goncourt and his brother Jules wrote a novel entitled Renée Mauperin and, in the summer of 1882, Tissot was asked by them to illustrate it. Tissot produced ten etchings and in all of which Kathleen Newton was depicted as the heroine of the novel.

Tissot’s first task on returning to France was to enhance his reputation with the French art critics. In order to do this, he put together a collection of over a hundred of his works, most of which he had completed whilst living in England and exhibited them at the Palais de l’Industrie with the centrepiece being his set of paintings entitled The Prodigal Son in Modern Life, which he had exhibited at his one-man show at the Dudley Gallery, London in May 1882. In one of the paintings from the set (The Fatted Calf), we see a young man stepping out of his rowing-boat on the Thames to join his family at lunch in a summer house where a sumptuous meal has been set out to celebrate his return. Despite Tissot translating all the titles of the paintings into French, the exhibition was coolly received with one critic scathingly describing Tissot as:

“…a Parisian of London now become a Londoner of Paris…”

In other words, as far as the French art critics were concerned Tissot had become too English for their taste. The only glimmer of hope for Tissot was that his pastel work at the exhibition was praised and during the 1880’s and 1890’s he turned more to that painting medium. One of his outstanding pastel on linen works was his 1895 portrait, The Princesse de Broglie. The lady was Joséphine-Éléonore-Marie-Pauline de Galard de Brassac de Béarn better known simply as Pauline, wife of Albert de Broglie, the 28th Prime Minister of France. Her pose is casual and yet the way she rests her hips on the table makes for an impressively alluring image. Tissot’s use of brilliant green pastels was to become his trademark.

Tissot, now back in Paris, sought to get himself back into Parisian society and would regularly frequent clubs and restaurants but the one thing he did consistently was to rise early and go to morning mass. He was disappointed that his exhibition at Palais de l’Industrie had not been received as well as he had hoped, and in 1883 he set about putting together a new series of fifteen paintings known as La Femme à Paris which looked at the life of Parisian women of different social classes at various occupations. He conceived a series of compositions focusing on women’s daily lives, from widowhood to flirtation, boredom in the countryside to belle of the ballroom, theatre to confessional.

Two years later the series was completed and they were exhibited at the Galerie Sedelmeyer in Paris in 1885 and in the Arthur Tooth Gallery in London in 1886. The theme of bustling Paris was very popular with artists in the 1890’s. The paintings were much larger in scale than anything Tissot had done before, his hope being that the monumental works would have an impact on critics and public alike. The Sporting Ladies one of the La Femme à Paris series, measuring 147 x 102cms, depicts a woman engaging the viewer as a participant in the action by her direct glance out of the picture. The event is a “high-life circus,” in which the amateur performers were members of the aristocracy.

Another large painting in the series was Without a Dowry. The setting is the Tuileries Gardens where we see a beautiful young lady dressed in black, who is a recently bereaved widow. Next to her, sitting down reading the newspapers, is her mother, also adorned in black. To the left, in the background we see two soldiers, one of whom is struck by the beauty of the widow and stares at her with an admiring gaze albeit he is reluctant to approach her. The subject of the painting highlighted the plight of young widows who, on the death of their husbands, were often left financially destitute. This was a very popular subject during the Victorian era.

The last painting in the series La Femme à Paris was completed in 1885. It was entitled Sacred Music and it depicted a young woman singing with a nun in the organ loft of a church. For this painting Tissot visited the church of S. Sulpice in Paris. As he sat in one of the church pews during the mass service he experienced a vision which was to change his life. He recalled the vision later:

“… As the Host was elevated and I bowed my head and closed my eyes, I saw a strange and thrilling picture. It seemed to me that I was looking at the ruins of a modern castle…..then a peasant and his wife picked their way over littered ground; wearily he threw the bundle that contained their all, and the woman seated herself on a fallen pillar, burying her face in her hands…. And then there came a strange figure gliding towards these human ruins over the broken remnants of the castle. Its feet and hands were pierced and bleeding, its head was wreathed in thorns…. And this figure, needing no name, seated itself by the man and leaned its head upon his shoulder, seeming to say…..’See, I have been more miserable than you; I am the solution to all your problems; without me civilization is a ruin’…”

Following this vision Tissot sat down and painted a picture of what he had seen in this vision. It was entitled The Ruins (Inner Voices). It has to be said that the setting of a modern castle as described by Tissot is not transferred to the painting as this rather looks like a scene from the Paris Commune risings which Tissot had witnessed. It is a moving portrayal especially the depiction of Christ. This painting marked the beginning of Tissot’s devotion to illustrating the Bible. Strangely enough it was these religious paintings which were to bring Tissot greater wealth and prominence than his earlier modern-day life depictions. There were many cynics, including his friend Degas, who believed Tissot’s religious conversion was more to do with the increased sale of his work than to his religious beliefs. Could this be true? To give Tissot the benefit of the doubt one has to remember that there was a great revival of the Catholic church and its preaching in France during the later part of the nineteenth century, which was a counter reaction to the anti-clerical spirit of the Third Republic.

It was not just the Catholic religion that Tissot embraced. He also took up Spiritualism and attended séances which had become very popular in the late nineteenth century and which had given him some comfort during the days following his wife’s death. In two séances Tissot attended, he was “visited” by an apparition of his beloved Kathleen, and despite one of the mediums later jailed for fraud, Tissot’s beliefs remained unshaken and he completed a work in mezzotint, L’Apparition médiumnique (The Mediumistic Apparition) in 1885. Tissot kept the picture in a special room in his house which he reserved for private spiritualistic séances.

This great interest in Catholicism led to the last great project embarked on by Tissot. He decided to dedicate his time in illustrating the whole of the Bible. This first stage of this mammoth task was to concentrate on the New Testament and Tissot started the illustrative work in 1866. Eight years later and with 365 illustrations completed his artistic labour was complete. Tissot was a perfectionist and to ensure the settings for the illustrations were accurate he made a number of trips to Palestine.

The first trip started in October 1885 and lasted five months. He would return again to this biblical land in in 1889 and 1896. Whilst in Palestine Tissot recorded the landscape, architecture, costumes, and customs of the Holy Land and its people, which he recorded in photographs, notes, and sketches. This enabled Tissot to paint his many figures in costumes he believed to be historically authentic, and the completed series of watercolours had great archaeological accuracy. Tissot’s typical daily routine was recorded by Cleveland Moffett, the American journalist, author, and playwright in the March 1899 issue of the McClure’s Magazine, an American illustrated monthly periodical which was very popular at the turn of the 20th century. He wrote:

“…six o’clock saw him out of his bed even on dark winter mornings and seven o’clock found him at the Convent Marie Réparatrice, bowing before the candles and listening to the chant of the kneeling women…….and then, after eating, set forth to work, riding through the streets of Jerusalem, a servant trotting besides him with colors and brushes in a basket, and a large umbrella for shade, and such other things an artist needs. Then would come two hours’ sketching the putting down of numberless backgrounds for the Christ story…… and after food [lunch] came another excursion within or without the city and two hours more work……After dining quietly, M. Tissot spent his evenings in reading and reflection…”

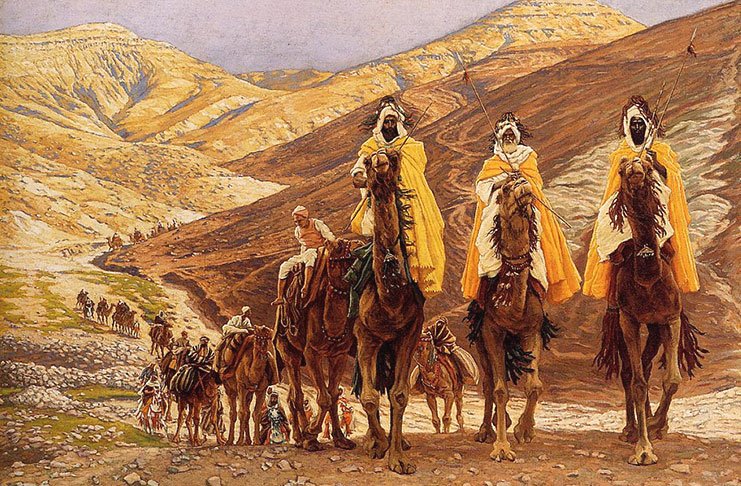

One of his finest works of the series was his opaque watercolour over graphite on grey wove paper entitled Journey of the Magi. The Magi are depicted in their flowing saffron robes being guided by the star. They have come from their individual lands in the east in their search for the new-born Jesus. The setting is the vast, arid landscape of the volcanic hills on the shores of the Dead Sea between Jericho, the Kedron Valley, and Jerusalem. The painting is a juxtaposition of beautiful shimmering masses of golden yellows, soft purples and rich browns. Look how Tissot has magically contrasted the highlights and shadows. The leading riders almost step out of the picture making us feel that we are almost there with them. The three wise men lead the procession. Tissot’s depiction of the three men differentiates their ages by the colour of their beards. All have weather-beaten darkened faces which is in contrast to the brightness of their golden robes. The long trail of men riding their camels spreads out far beyond the mountain range and vanishes into the distance.

Once Tissot returned to Paris he set about rendering his sketches into actual paintings. The finished series became known as Tissot’s Bible and he wrote a foreword for the tome. Although he no doubt wrote from the heart the solemn words of the introduction now appear self-righteous, mystical and somewhat embarrassing. Cleveland Moffett, the American journalist, author, and playwright in his article about James Tissot wrote an article for the March 1899 issue of the McClure’s Magazine entitled Tissot and his Paintings of the Life of Christ, in which he talked about Tissot’s artistic methodology:

“…M.Tissot, being now in a certain state of mind, and having some conception of what he wished to paint, would bend over the white paper with its smudged surface, and looking intently at the oval marked for the head of Jesus or some holy person, would see the whole picture there before him, the colors, the garments, the faces, everything that he needed and already half conceived. Then, closing his eyes in delight, he would murmur to himself ‘How beautiful! Oh, that I may keep it! Oh, that I may not forget it.’ Finally putting forth his strongest effort to retain the vision, he would take brush and color and set it all down from memory as well as he could…”

In his watercolour, Jesus Goes Up Alone onto a Mountain to Pray, we see Jesus seeking solitude for prayer following the miracle of the loaves and fishes, at the summit of a mountain. It is a dramatic, some would say, melodramatic image, seen from below as we look up and see Jesus depicted, arms held out, against a night sky, with his gleaming white robes backlit by the radiance of the stars and the crescent moon.

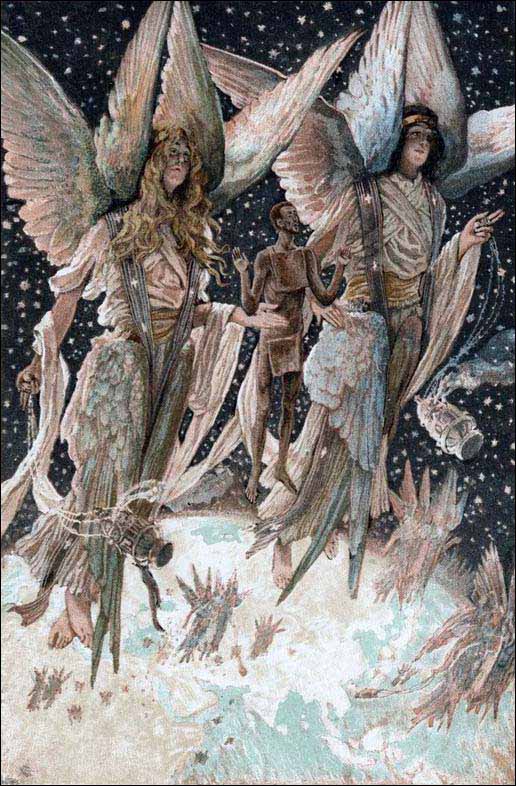

In his work, The Soul of the Penitent Thief in Paradise, Tissot depicts the tiny figure of the thief being literally lifted by angels into orbit above the earth. Maybe the work is more to do with spiritualist apparitions than religious visions.

Probably the quirkiest, and of questionable taste, is his painting, What Our Saviour saw from the Cross. Look carefully at the centre foreground and you will see the feet of Christ and we, as mere spectators, are literally made to feel that it is us who is hanging from the cross. It was this kind of realism which appealed to the Catholic faithful in the 1890’s.

Tissot even included a self-portrait in one of his biblical scenes, Portrait of a Pilgrim. Tissot closed the published volumes of The Life of Christ with this funerary self-portrait and a plea to the reader to pray for him. In the depiction we see him standing among articles associated with rites for the dead: tapers, a draped coffin, wreaths, and holy water. In the background, a large wreath surrounds the distinctive “JTJ” monogram with which he signed some of his works. But there is more to this picture than first meets the eye. While Tissot raises his right hand in a gesture of benediction, his left hand seems transparent, almost like a ghostly apparition. Look how the lit candles flicker, almost as if a sudden gust of air—or a spirit—has passed through the room.

Tissot’s Bible was an immediate success and the Paris art world was thrown into turmoil. The series became a talking-point in artistic circles. An exhibition of 270 of the 350 pictures was held in 1894 at the Salon du Champs-de-Mars and it was the greatest public success of Tissot’s career. The public were overwhelmed by the paintings with some women sinking to their knees and even crawling around the rooms in reverent adoration. After years of criticism Tissot had finally given the public what they desired– a mystical godliness which encapsulated the religious ambience of the day. After the Paris exhibition the illustrations were shown in London and, in 1898, toured America where the entrance fees to view Tissot’s work raised in excess of $100,000. In 1900, the Brooklyn Museum purchased this set of 350 watercolours, popularly known as The Life of Christ, and to this day, they remain one of the institution’s most important early acquisitions.

The success of the exhibitions led to a publication of The Life of our Lord Jesus Christ with its 350 illustrations by Tissot. It was first published in France in 1897 and later in both England and America. Tissot received a million francs in reproduction rights from the French publisher alone. The success of the book and the paintings ensured James Tissot would be a very rich man for the rest of his life.

Part of the Old Testament Series.

Tissot inherited the Chateau de Buillon from his father in 1888 and from that date onwards divided his time between there and his house in Paris. He lived in considerable style and surrounded himself with servants and relatives, one of who was his niece Jeanne Tissot, whom he left the chateau and all its contents when he died. After the tremendous success of the Life of Christ series he decided to illustrate the Old Testament and made his final trip to the Holy Land in 1896. Sadly, Tissot never completed his Old Testament series but before his death in 1902 he had completed ninety-five of the illustrations and these were shown at an exhibition at the Salon du Champs-de-Mars in 1901.

(1836-1902)

Whilst overseeing renovations in the gardens at Chateau de Buillon he caught a chill and died on August 8th, 1902, aged 66. At the time of his death his reputation had begun to decline but nowadays his works of art are appreciated by more and more people.

Most of the information I used for the five parts of the James Tissot blog came from information I found in Christopher Wood’s 1986 biography of Tissot which is an excellent read, full of beautiful pictures.

If you would like to read the full March 1899 article about James Tissot as it appeared in the McClure’s Magazine by Cleveland Moffett, entitled Tissot and his Paintings of the Life of Christ, then copy and paste the URL below into your browser:

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015030656113;view=1up;seq=415