Today I want to focus on the early life of one of the greatest nineteenth century French landscape painters, Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot. He was one of the leaders of the Barbizon School and a master of plein air painting. The Barbizon school, which existed between 1830 and 1870, acquired its name from the French village of Barbizon, which is situated close to the Fontainebleau Forest. It was here that an informal group of French landscape painters gathered. Other great luminaries from this group were Théodore Rousseau, Jean-François Millet, Charles-François Daubigny and Constant Troyon, to mention but a few.

Corot was born in Paris in 1796. He was one of three children. He had an older sister Annette Octavie and a younger sister Victoire Anne. His father, Louis Jacques Corot, a Burgundian, was a cloth merchant and his mother, of Swiss origin, Marie Françoise Corot née Oberson, came from a wealthy wine merchant family of Versailles. Camille’s parents were members of the so called bourgeois class, characterized by their sound financial status and their related culture, which their money allowed them to enjoy. Following their marriage his father managed to purchase the hat shop, which his mother had worked in and he then gave up his career and helped her manage the business side of the shop whilst she carried on with her design work. The family lived over the shop, which was situated on the fashionable corner of Rue du Bac and Quai Voltaire, at the end of the Pont Royal Bridge. From the windows of his room above the shop, Corot was able to see the Louvre and the Tuileries. It could well be that the beautiful views Corot witnessed from his room had an influence on his art. Their shop was very popular with the Parisians who always wanted to have the latest in fashion accessories. It was a very successful business venture and on account of his parents’ affluence, Corot, unlike many of his contemporaries, never had to endure the hardships brought about by poverty.

His parent enrolled Camille in the small elementary school in the Rue Vaugirard in Paris and he remained there until he was ten years old. The following year, 1806, his parents then sent him to the Lycée Pierre-Comeille College in Rouen. During the time there, Corot lodged with the Sennegon family, who were friends of his father. The Sennegon family were great lovers of country walks and they would often take Camille Corot with them. Over the five years he lived with the Sennegon family, Camille too built up a love for the countryside and nature and it was this love which would influence his work as a landscape painter and it was this very region that Corot depicted in his early paintings

Corot left Rouen and the Sennegon family home and, at the age of nineteen, he completed his formal education at a boarding school in Poissy, near Paris,. Corot was not remembered as a clever student. He never won any academic awards and did not show any interest or ability in art. After leaving college his father arranged a number of apprenticeships for his son with a number of cloth merchants but Camille never settled and disliked the business practices inherent in that line of work. Corot had discovered another love which soon consumed him and his time – Art. In 1817, Corot started to spend all of his evenings painting, attending the art school, Académie Suisse in Paris.

In the same year, his father purchased a country home at Ville-d’Avray, eight miles west of the centre of Paris. Camille loved the house and the surrounding area with its woods and small lakes. Again, as was the case when he lived in Rouen, Corot was able to appreciate the beauty of nature and the urge to record what he saw in his sketches and paintings. Ville-d’Avray and the surrounding area were to be the focus of many of Corot’s en plein air paintings throughout his life time. His bonding with nature, once again, only served to reinforce his desire to paint. The countryside around Ville-d’Avray provided Corot with an immense amount of subjects for his “en plein air” paintings all his life. Étienne Moreau-Nélaton an artist and art collector and contemporary of Corot commented on Corot’s love of the Ville d’Avray when he said:

“…Providence created Ville-d’Avray for Corot, and Corot for Ville-d’Avray…”

In 1822, by the time Camille was twenty-six years of age, he had spent almost eight years working for various cloth merchants and had enough of this life. In Vincent Pomarède & Gérard de Wallens, 1996 book Corot: Extraordinary Landscapes they quote Corot’s recollection of his conversation with his father:

“…I told my father that business and I were simply incompatible and that I was getting a divorce…”

The one thing that Camille did gain from working with textiles at the cloth merchants was it taught him about colours, patterns, textures and design and it could be that it was then that he began to explore painting as a possible career. His father had equally had enough of his son carping about working for fabric dealers and so asked him that if he wasn’t to follow him in his trade then what did he want to do. Camille’s answer was unequivocal – he wanted to be an artist.

However, to do this, Camille needed some extra financial help. Sadly, a year earlier, his younger sister, Victoire-Anne, had died and her annual family’s allowance of 1500 francs could now be made available to finance Camille’s artistic ambitions. This modest funding was to support Camille comfortably for the remainder of his life. His parents were not happy with their son’s decision to become an artist, believing life as such led to just one thing – poverty.

With the financial assistance from his parents, Corot established an artist’s studio at No. 15 Quai Voltaire, a road which ran along the banks of the River Seine and was located close to his family home. He, like many aspiring artists of the time, studied the works of the Masters in the Louvre and was initially tutored by the French painter, Achille-Etna Michallon. After the passing of Michallon, in 1822, Corot moved on to the studio of the French historical landscape painter, Jean-Victor Bertin. It was under the auspices of this painter that Corot started combining the French neoclassical with the English and Dutch schools of realistic landscape art in his paintings. Corot at the same time began sketching nature en plein air in the forest of Fontainebleau near Paris and in Rouen.

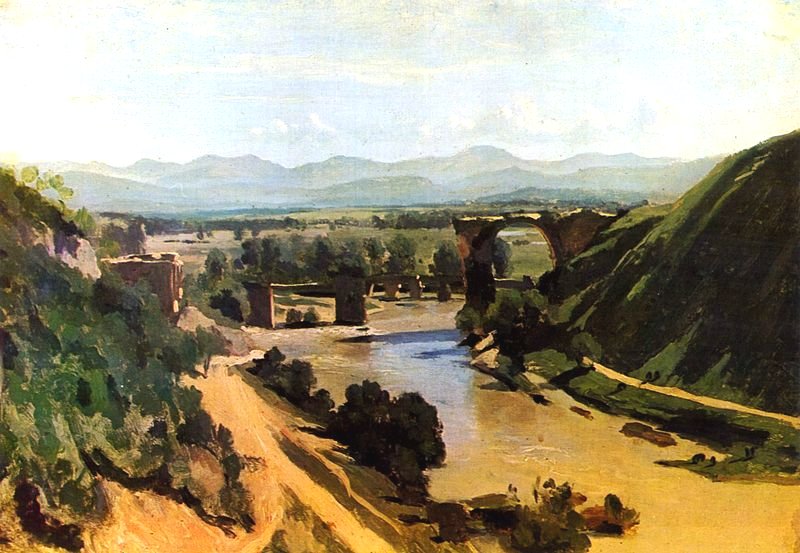

In 1825 Corot decided that to enhance his artistic ambitions he had to follow the well trodden route of artists and head for Italy. Here he wanted to study the landscape of the Italian countryside around Rome, the Campagna. He remained in the area for almost three years and in 1826 he took a painting trip to the Nar Valley and the hill top town of Narni which brings me to My Daily Art Display’s featured paintings by Corot entitled View at Narni, which is currently housed in the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa and the preliminary oil sketch, The Bridge at Narni, which can now be seen in the Louvre. This was initially painted by him as a study for that final work. Painters in France at the time were encouraged to paint outdoors (en plein air) but the results were not looked upon as the finished works but merely as aides-mémoire for how the light and the atmosphere was at the time. The artists would then take these sketches to their studios where he or she would complete the finished Classically-balanced composition. The preliminary sketches were then just filed away and were never exhibited. Now of course, these plein air sketches are very valuable and of great significance as they highlight the immediate and unmediated perception of the scene as seen through the eyes of the artist. It is therefore interesting to look at the differences between the preliminary topographically true vision of a landscape and the finished work which may in some way have been somewhat idealized in order to boost the artist’s chance of selling the painting.

Today I am featuring both Corot’s preliminary sketch and the completed painting depicting the Bridge at Narni. He came upon the town of Narni, on the River Nera in September 1826. This Roman Bridge of Augustus was built in 27 BC, and was one of the two tallest road bridges ever built by the Romans. The Narni Roman Bridge was 160 m long and its remaining arch is 30 m high. Corot was not the first artist to incorporate the bridge in one of his paintings as his erstwhile tutors, Achille-Etna Michallon and Edouard Bertin both completed works which depicted the structure.

Preliminary oil sketch

If we look at the preliminary oil sketch above we can tell it is a first attempt as the foreground is formless in detail. Maybe this is due to the fact that as a plein air artist he was not concentrating on the details close to where he stood or sat at his easel. His concentration would be solely focused on what he saw in the mid-ground and the background and he would have been absorbed by the aspects of light and shade at the very time he was putting brush to canvas. This sketch of Corot’s was highly acclaimed by artists and critics alike for its naturalness and for its captivating breadth of vision.

When Corot returned to Paris the following year he set to work on his final oil painting of the bridge at Narnia. He decided to put forward two paintings for exhibiting at the 1827 Paris Salon. He wanted them to be two contrasting works. One would depict a morning landscape whilst the other would depict an evening landscape. For the morning landscape he submitted his final View at Narnia, the one shown at the start of this blog, whilst putting forward The Roman Campagna (La Carvara) as the evening landscape scene. This latter painting is presently housed in the Kunsthaus, Zurich. This final rendition of the painting, View at Narni, is much larger, at 68cm x 93cm than his preliminary oil sketch, Bridge at Narni, which only measures 34cms x 48cms.

When Corot set about “transferring” the details from his preliminary sketch on to the canvas for his final version he had to tread a fine line when it came to topographical integrity and idealised perfection. This was the normal practice of landscape artists of Corot’s day. It was expected of the landscape painter not to just depict a photo-like depiction of a scene, but bring to the painting what the likes of Claude had done before – a neoclassical ennoblement.

In Peter Galassi’s 1991 book, Corot in Italy, he talked about Corot’s desire to emulate the great landscape painters of earlier times and he knew he had to find a way to reconcile traditional painting objectives with those of plein air painting:

“…So deeply did Corot admire Claude and Poussin, so fully did he understand their work, that from the outset he viewed nature in their terms….In less than a year (since his arrival in Rome) he had realized his goal of closing the gap between the empirical freshness of outdoor painting and the organizing principles of classical landscape composition..”

The artist had to bring an academic approach to bear on his initial vision. Look how Corot has changed the foreground from being a steep slope in his preliminary sketch, which was how it was, to terracing and as was often the case in academic landscape works he has added a path, in the left foreground, and on it we see some sheep and goats. Corot has added shepherds tending their flock and near to the cliff edge, he has added a couple of umbrella pine trees synonymous with and symbolic of the Roman countryside. This final version has now become a typical example of a Neoclassical landscape.

Corot must have liked the final version, for it remained with him and hung in his bedroom until he died. The art historian of the time, Germain Bazan, commented on the difference between the two versions saying of the original plein air oil sketch:

“…a marvel of spontaneity in which there is already the germ of Impressionism, [while] the Salon picture, even though it is painted in beautiful thick paint and with great delicacy, is nonetheless a rather artificial Neoclassical composition…”

Kenneth Clark compared the two saying that of the two versions:

“… it [the preliminary sketch] is as free as the most vigorous Constable ; the finished picture in Ottawa is tamer than the tamest imitation of Claude…”

I will leave you to decide whether you prefer the original, topographically accurate sketch or the somewhat idealized final version. Below is how the bridge appears today.

I barely recognized the 2 paintings as being of the same subject. Remarkable.

Great story. Thank you. I love the final version. The detail is fantastic. Do you know how many of these final versions he may have painted?