Just over a fortnight ago an elderly relative of a friend of mine died. Last week I went to the funeral service and just prior to the ceremony I was asked if I would like to view the body lying in the coffin before the lid was closed. I said that I would like to pay my last respects to the deceased. I was somewhat prepared for what I might see but when you gaze down at the lifeless body it still comes as a shock. Notwithstanding how well the funeral home people have prepared and dressed the body, the viewing of the deceased is still a harrowing experience.

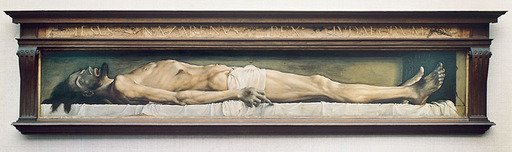

The other day I came across a painting by Hans Holbein the Younger, which reminded me acutely of my experience and I decided to make it My Daily Art Display for today. The oil and tempera on limewood painting, which can be found in the Kunstmuseum in Basle, is entitled The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb and Holbein completed it in 1521. The painting is lifelike in size, measuring 2 metres long and just 31 centimetres high (79 inches x 12 inches) and depicts the dead Christ lying stretched and unnaturally thin in a wooden tomb. The dimensions of the painting create a disturbing effect. The painting has an almost claustrophobic shape. Many artists, such as Caravaggio, Delacroix, Titian and van der Weyden have painted The Entombment but looking at Holbein’s portrait of the dead Christ is probably as shocking a picture as one is ever likely to come across. Grunewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece showing the ravaged and distorted body of Christ on the cross and The Deposition, his lowering to the ground, shows the strain on the body of Christ which one can barely imagine but Holbein’s Christ lying before us, dead in his tomb, is both intense and overwhelming.

One has to wonder what Holbein intended for this piece of art of such unusual dimensions. Was it meant to be a free-standing painting or maybe it was to be a predella below an altarpiece?

Borne above the painting by angels holding the instruments of the Passion is an inscription in brush on paper:

“IESVS NAZARENVS REX IUDAEORUM”

There is a stark realism about the painting and I can only imagine that to stand in front of this life-sized work of art must be both awe-inspiring and shocking. I am told that when you look at the painting, it is as if the tomb has been set into the wall of the gallery because Holbein has created a three-dimensional illusion. The physical depiction of the body is realistic. It is said that Holbein used a body dragged out of the Rhine as his model. Looking at the body of the dead Christ is just like the experience I had a week ago when I gazed at the dead person, albeit she was clothed, but her hands, wrist and face were uncovered and discoloured. Every physical feature of death is portrayed in this painting. The body of Christ has the marks of the crucifixion. We look in horror at the blood-caked wounds in the back of his hand and his feet, where the nails had penetrated. We see the wound in his side which had been penetrated by the lance. All the wounds are turning a gray-green and becoming swollen, due to the onset of gangrene. Surprisingly, there are no marks on Christ’s forehead from the crown of thorns.

Let us look at some of the detailed work this great artist has given to this painting. The blackened feet of Christ lie almost to the end of the stone-walled enclosure. The bones of his body push against the flesh like spikes emphasising the hollowness of his ribcage. String-like muscles press against the lifeless yellow skin. Look carefully at the face of Christ which is slightly tilted towards us. The hair of Christ spills over the stone block which has been covered with a white shroud. His beard points upwards towards the low roof of this wooden box-like tomb. His right hand balances on the edge of the dishevelled shroud. All but his middle finger is curled inward and we can almost feel the pain the dying Christ felt as his life ebbed away. His bony middle finger points, to what we do not know. Except for the deathly pallor we may believe he is still alive. His eyes and mouth are open. We could be forgiven in thinking we are at the bedside of a dying man who looks heavenwards as he exhales for the last time. Why did Holbein paint the dead Christ with his mouth and eyes open? Could it be that Holbein is reminding us that even in death Christ nonetheless sees and speaks? Is it to remind us that even from the decay of the tomb Christ did rise again on the third day? In the fifteenth and sixteenth century, works of art similar to this, intensified the imagination of the observer with regards to the suffering Christ had to endure and by doing so giving an intensity to people’s meditations on Christ’s Passion.

This panel painting has attracted fascination and praise since it was created. The Russian author Fyodor Dostoyevsky was wholly captivated by the work. It is said that in 1867, his wife had to drag her husband away from the panel lest its grip on him induce an epileptic fit.

I stumbled upon this site through sheer serendipity.

Simply beautiful in quality and word.

Amazing! And I just came by this picture in another setting by Fridtjof Hoel. A very disturbing mage.

In a clearer image you can see that there is a black board in the background right behind his feet and it has writing on it. Do you know what that is?

I think Holbein is reminding the viewer that even as Christ lived as a man, he wholly died as any other man would die. That is what so impressed Dostoyevsky when he saw it.

I found your site because of Kahinde Wiley’s magnificent 2008. “Sleep” portrait, which is now on display at Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, NE. He modeled it after this Holbein painting. I hope to read more of this blog.

This painting plays a somewhat important role in Dostoyevsky’s “The Idiot.” https://humanities.byu.edu/dostoevskys-measure-of-faith/

The degree of decay indicates that he has been deceased for much longer than 3 days and never did rise from the dead